The Fixity of Signs

The flutter of an eyelash, the drop of a book, a burst of laughter

His forefathers were magicians who saw judgment.

His grandfathers were doctors who saw miasma.

His father was a psychiatrist who saw disorder.

They are all gone, their work superseded, eclipsed like tiny suns behind a greater moon. They are replaced by their progeny: the semiotist who knows that all disorders are disorders of status. Like the psychiatrists, the semiotist knows that external reality is entirely a conjuration of the mind, but he knows a deeper truth: reality is a web of relations between minds, the signs and symbols that create (and destroy) men and women, that all suffering comes from not knowing one's place in that web. The semiotist sees signs.

Those afflicted by status disorders can do serious harm to themselves and others. It is best to call the semiotist as quickly as possible. "There are two types of status disorders", he explains to the patient and their fretful loved ones in his dimly lit office, "Those who believe themselves to be much higher status than they truly are, and those who believe themselves to be much lower status than they truly are." The positively disordered humour the semiotist, some even believe they are higher status than him. The negatively disordered are confused but become calmed by his confidence (the doctors of old knew that patients benefited from calm, though they did not believe the patients deserved it).

The loved ones have been carefully instructed not to interrupt. Their private thoughts have already been communicated to the semiotist: My husband thinks a turn to stare at the sky signifies suppressed ardor instead of disgust. He has become untethered from the order of things and it is going to ruin him.

The semiotist feels their pain and he feels the victim’s pain. A disordered subjective sense of status is impairing the true, intersubjective, status of the victim. It is crucial that the semiotist repair them before any further harm.

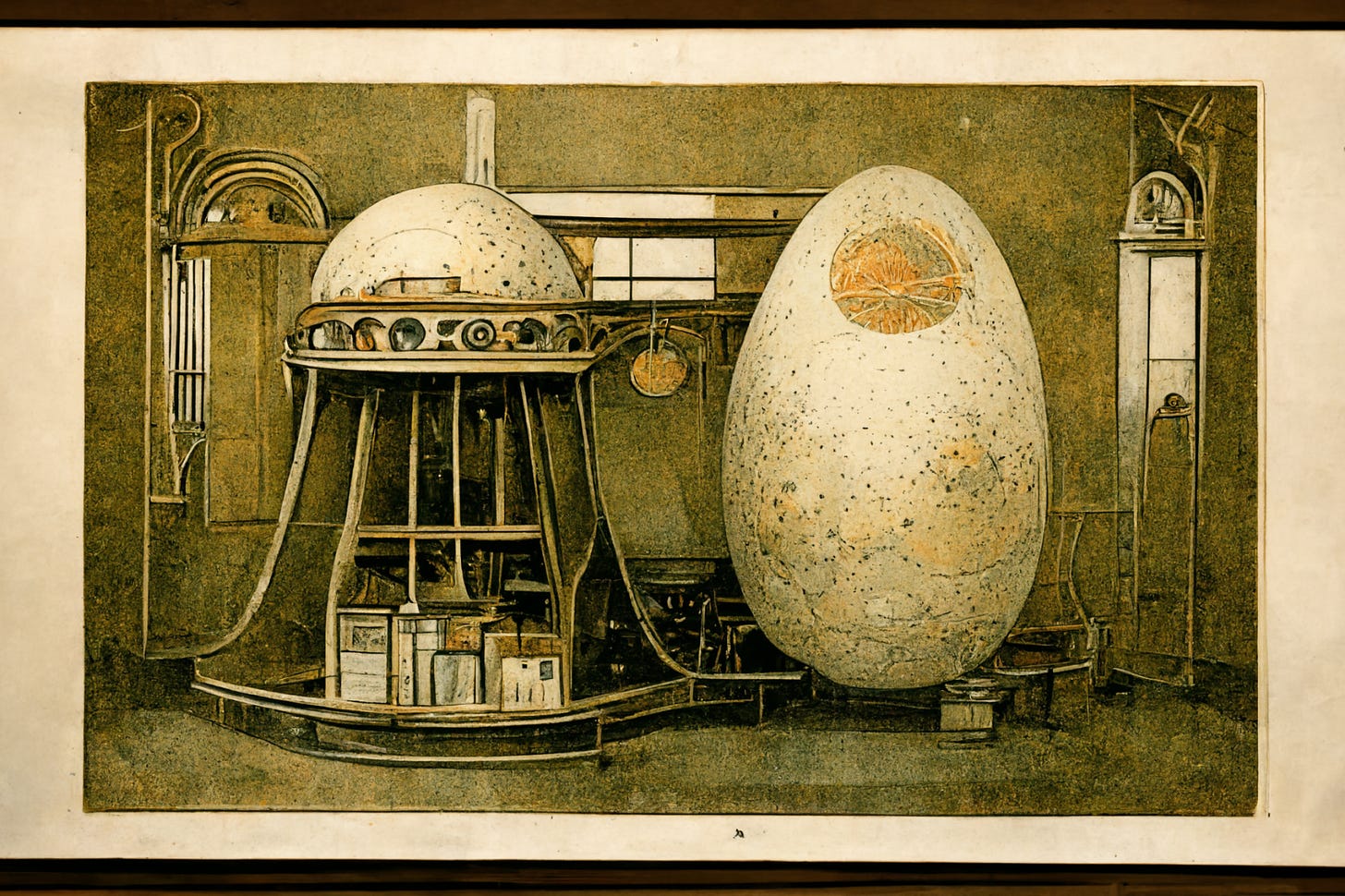

"The culprit in all status disorders," he says, "is a small portion of the brain that we have only come to understand in recent years. This portion, a cluster of neurons, tracks one’s place in the great web of semiotics, but it can become abnormally dampened or enflamed." As he talks he prepares his machine, which is like an enormous egg in the corner of the room. After his patient lifts himself (for it is nearly always a man disordered) into it the doctor turns off even the dim light in the room. It is a pleasant machine, the kind that makes one so comfortable that one realizes he prefers it to standing. It serves as examiner and in the next session it will serve as surgeon.

It is remarkable how similar the semiotist's methods are for the status-low and the status-high. While they are in the machine, he asks them ten or so questions, all of a similar nature: What is the meaning of a broken flower? A request to walk in cloudy weather? Do other men clap you on your back?

By asking such questions, he induces his patients to produce such personal signs as he can quickly assimilate (the quiver of a cheek, the pitch of the response, the pun). Then he can ascertain the crucial fact: Does the person know their place in the hierarchy of signs? Is the person tracking their status successfully or not? But he has already heard from the family, and the family is usually correct: My brother isn’t a chad at all, he hasn't had a girlfriend in years. Or: My father thinks he’s an important researcher but hasn't published a paper in decades. Still, the semiotist must ascertain the truth of the matter.

Upon such confirmation, the semiotist will schedule the surgery. On that day, he will direct the machine to make certain incisions so as to re-order the defective neurons. It can take many surgeries to properly align the neurons but recovery is fast. Patients leave the dark room of the semiotist for the light of the day and are happy to feel that they simultaneously enter the light of truth: They know their place relative to everyone around them, just like everyone around them has always known. The signs that gush forward from the people around them now make sense: The flutter of an eyelash, the drop of a book, a burst of laughter. These no longer confuse the patient, no longer lead him down the wrong path. He knows his status perfectly.

The semiotist is high status. He has willed himself to be, which does not work for any of his patients, perhaps because he did it first. He is hated by the psychologists, which entertains him, for it is high status to be hated and low status to be forgotten (like the psychologists). He is loved by all who love the truth. He is consulted occasionally by governments on both the left and the right. His tastes are elegant, of course, but what is important is that they change slightly faster than those of others. When his circles become engaged with the thought of Gilles Deleuze, the French Nietzschean, they are enthralled when he mentions that of late he prefers Pierre Klossowski, the obscure Nietzschean who showed that God's death is always already the death of his successor, Man.

His opinions are full of affection for the opinions of his interlocutors, and these interlocutors leave the conversation feeling that the semiotist has raised them up. In truth, he could point at a man and make him high status through his approval. But this would be magic, and to work with magic is to be a servant to the flux of phantasms. No, the semiotist is a master of neurons, signs, and man, and through his wisdom and strength he is capable of healing beyond magic.

The semiotist has an assortment of wives, girlfriends, and mistresses. Yet the press can find no gossip by which to poison him. It is not only that he does not profane himself with lewd messages -- It seems that he doesn’t engage in physical intimacy at all. While it is plausible that he is entirely private with such things, he has never produced progeny of his own.

When asked of it on a podcast (which can be high or low status, depending on the will and power of the guest), he replies only after a long period, as is his wont. He admits, no, he is not sexually intimate with any of the women who surround him. He explains that the entirety of his affections is reserved for his patients, who deserve his full attention and care. "Come on", asks the host, who will die of an overdose in a few weeks. "Not at night? What are they even for?"

The semiotist laughs in a way that reassures all listeners of his strength. But then he says, louder and louder: “Which signs would you have me abort? The quickening of the breath? Meetings in gardens? Letters without reply? The look that lingers? The sonnet recitations? The repeated and desperate offers of aid? The half-jest matchmaking?” The host is leaning back in his chair, astounded at the semiotist’s anger. He shouts: “How could the sign ever be inferior to that which it signifies!”

Wow this makes me smarter. Ok but I’m a little confused at the ending...the semiotist shouts? Or the podcast host? I thought the thing signified is greater than the sign...if the host shouts that it seems to make him in agreement with the semiotist, so why the anger...at first I thought the host was being more insightful to shout basically why enjoy all these signs of romance rather than the real thing? But then the wording is how can the sign ever be inferior to what it signifies...meaning it’s not inferior...so I’m confused. But if semiotist shouted then makes sense, it fits his delusion. But last person subject is who the pronoun signifies, “He shouted” which would be the host...so who shouts?